Accurate and reliable pain measurements have always been relevant for pain research and clinical practice. One of the most widely accepted ways to measure pain is visual analogue scales (VAS). Patients are asked to match the length of a line with their pain intensity. Although simple and effective, researchers have frequently debated whether VAS ratings could be improved. With this in mind, some investigators hypothesized that functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) could be used to accurately and objectively measure patients’ pain and at the same time provide an unbiased representation of a patient’s pain experience.

Accurate and reliable pain measurements have always been relevant for pain research and clinical practice. One of the most widely accepted ways to measure pain is visual analogue scales (VAS). Patients are asked to match the length of a line with their pain intensity. Although simple and effective, researchers have frequently debated whether VAS ratings could be improved. With this in mind, some investigators hypothesized that functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) could be used to accurately and objectively measure patients’ pain and at the same time provide an unbiased representation of a patient’s pain experience.

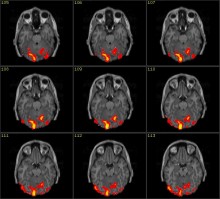

A recent study by Wager et al. (N.Engl.J.Med. 368:1388-97) examined healthy volunteers to see whether pain related brain activity would accurately reflect their self-rated pain experience. First they identified pain specific patterns of fMRI activity in 114 participants. Subsequently, they tested the sensitivity and specificity of the brain pain signature in comparison to a painless warm stimulus. Following this analysis, a third study identified brain regions activated by emotional or social pain and compared them to brain activity during physical pain. The fourth, and final, study tested the sensitivity of the obtained measures to analgesic manipulations.

This interesting study described the fMRI “pain” signature was 94% sensitive and specific and could distinguish pain from nonpainful warmth, pain anticipation, and pain recall. This “pain” signature was significantly attenuated when an analgesic agent was administered. After these studies the investigators concluded that fMRI is useful for the assessment of noxious heat in healthy individuals.

It is important to remember that pain is personal and therefore a brain scan will never completely capture this experience. Thus self-report of pain is the gold standard that brain imaging has to be compared to. Thus, why use fMRI and not self-report in the first place? Brain scanning is cumbersome and expensive. The answer is that brain scanning is invaluable in identifying the brain mechanisms involved in the pain experience. Furthermore, brain scanning of pain may be very helpful in partially conscious persons, in very young children and in cognitively impaired adults. However, there is no evidence that fMRI can reduce variability of pain ratings or is more sensitive to pick up changes in pain than self-report. For this reason, the specific brain signature identified in this study should not be used in most clinical settings to evaluate patients’ pain experience. Additionally, this study was conducted exclusively on healthy individuals and patients suffering from chronic pain conditions may exhibit a different and less useful pain signature than healthy individuals. In conclusion, this study represents an important step in the use of functional brain imaging to evaluate important pain mechanisms. In the future, functional imaging of pain may be useful in patients undergoing surgery or other situations when self-report of pain is not possible. Otherwise self-reported measures of pain will remain the most important method in evaluating pain.

Meriem Mokhtech, BS

Senior Laboratory Technician

UF Center for Musculoskeletal Pain Research